The murder of beauty & the worship of ruins

A look into the spiritual death of our age through architecture

The Murder of Beauty

Throughout most of my teenage and adult life, I’ve come to meet a wide variety of people, who, often unknowingly, betray their principles with their actions. Some of them have been acquaintances of mine, others have been friends. Obviously, I hold no animosity against them, in fact, I quite like them, but the issue still stands. The particular “betrayal” I will discuss today is in regards to architecture. “but architecture?”, you may ask, “what is there to betray in regards to it?”. This is the question which I will seek to answer in the first portion of this article. But, before that, I will begin with a short story.

Around the spring or summer of 2020, while Covid lockdowns were being lifted for the first time, I was bombarded, on social media, with a variety of people I knew travelling to plethora of places around the world. One day in particular, while I was checking Instagram stories on my personal account, I remember coming across a certain girl from High School, who I knew to be a very dedicated progressive activist. She was showing off her travels in Rome and the rest of Italy, posting pictures of wondrous Catholic Cathedrals and the Gold-clad Baroque halls of Renaissance or Enlightenment-era palaces. She had not changed at all in her views, as stories about trans acceptance or racial representation in films had made abundantly clear to me, but despite that, there she was in the cathedral, there she stood next to the tombs of knights and bishops, there she went, photographing former and current aristocratic residences. She was not alone, others with similar views had done the same, but, as I was tapping my finger from one story to the next, a new thought occurred to me.

“How could it be that this person, who constantly attacks the church for wasting money on grand temples instead of feeding the poor more, is stepping into some of the most grandiose and -in her view- wasteful of these religious buildings with awe? How is it that she can even walk into the homes of the supposed archaic tyrants of Europe, those old-fashioned aristocrats, and admire these places?”

It was a simple thought, but it triggered an avalanche in my mind. A few months later, I would hear the same critique of “Liberal Tourism” on the channel of Dave the Distributist, a well-known neo-reactionary and traditional Catholic figure on the e-Right. His points informed my disorganized thoughts and made them more coherent.

This gets us nicely to the first part of our article, an exploration of the bizarre phenomenon that is “liberal/Progressive historical tourism” and why it actually is hypocritical for them to advocate what they do and then admire what they (directly or indirectly) mock.

Many may retort that - “well, these buildings are still beautiful and can be liked for their aesthetic, even if the purpose and construction of them was wrong”.

The problem with that thought is that the aesthetic directly fits into the ideological / spiritual framework these buildings are meant to support. Churches are awe-inspiring on purpose, because they wish to evoke the feeling of contact with God in all His vastness and power. Palaces are grand and Castles imposing for similar reasons, the former is meant to impress to the beholder that the person who resides in it has a certain grandeur and nobility, the latter is trying to showcase that the one who lives in it is powerful and fearsome. Victorian Gothic tombs are brooding and foreboding because they represent their function as burial places well (something fellow Goth fans and admirers, like my younger self, can certainly appreciate even today).

To fall for the symbolism of the buildings is a spiritual act in itself. It is a recognition of these attributes to the people who built these things, how could that not legitimize them? especially when the feelings being exhibited are deep and uplifting, as a sense of awe often is. When the Cathedral produces in someone the awe of the Divine, they no longer have the right to say it is a “useless waste of money that should have been spent on the poor”, they have personally experienced exactly its use and are in fact glad that they did so.

Another common attempt at rebuttal would be: - “we can still build such great and awe-inspiring things without needing aristocrats or priests holding authority over us! they could be monuments to the people!”.

This has, in fact, been tried, in the aftermath of the American, French and Russian revolutions, both in a liberal-capitalist-individualized sense, with statues of George Washington, Robert E. Lee, Cecil Rhodes and other noble, valiant or enterprising great men, from otherwise liberal and democratic governments, and in a popular-socialist-collectivized sense with the buildings “of the people” and worker statues or art of the Soviet Union or adjacent socialist states.

One could ask whether these buildings and statues truly evoke the same feeling in people as their pre-modern counterparts, but I will not dwell on this, since the very people who mock the church and remaining aristocracy are also just as likely to hate the statues of “Capitalist profiteers” / “Racist warmongers” and of “oppressive tyrannies which do not represent true socialism™”. In truth, it seems like these people have torn down every framework under which such works could be produced, even the ones of potentially inferior quality.

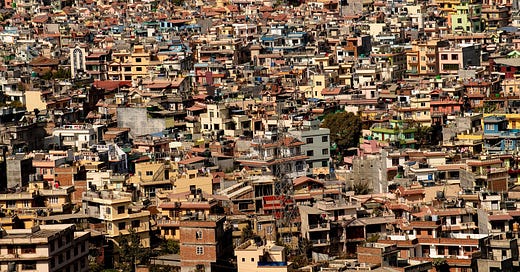

Most of the population lives in ugly concrete jungles, with cheaply built apartment complexes from the 70s and 80s everywhere. We know how that looks and what we think about it. It is so boring and ugly that we spend almost no time thinking, let alone stopping to admire it. It is just there, it performs a simple function and that is the end.

Even for someone like myself, who is an aficionado for a sort of 70s/80s cyber-futurism, it is difficult to appreciate the actual architecture of buildings today. The main appeal of such neo-futurism is the way it draws men to artificial light like moths, its merit comes from the glowing windows and LED signs that illuminate the night sky. Even with such appreciation in mind, it must be said that this conception bears a heavy cost, blocking out any chance of seeing a star-filled sky, something just as, if not more, beautiful than the lights being praised.

- “Then, why can’t we just enjoy what has already been built , even if we think it a waste to build more?”

Because, why would you not want to produce more works of beauty? Why must we dwell on the remnants of past civilizational states for our inspiration? How could the states which produce such great works really be considered as unequivocally evil, whereas our age of gray, dull, mediocrity and ugliness be considered good?

The left, as it formulates itself today, is even more hateful towards beauty than it has ever been historically. It simply refuses to see any value in valorizing anything through actual works of a transcendent character, partly because it transparently rejects the transcendent, and partly because it is much more comfortable and at peace with twisting already beautiful depictions to its own ends, marring the beauty of the original in the process. All you need to do, to see the truth of my point here, is to go and watch Netflix adaptations of older films and franchises, odds are, the older one had richer artistic, aesthetic and story-telling quality than its most recent adaptation.

This brings us to the second portion of the article:

The Worship of Ruins:

Unfortunately for all of us, this is not a problem that only the political Left must contend with. The Right has the exact opposite problem: it suffers from an inability to conceptualize new forms of beauty in architecture, dress, style and city layout.

Even the bold experiment of someone like King Charles III of the United Kingdom, with his “personal project” town of Poundbury, falls short, no matter how impressive it is, because it treads no new ground. All it does is try to develop a new “low-tech” mix of neo-classicism and traditional British architecture in the middle of England. I personally adore it and I think it is necessary as a statement of antithesis to rapacious modernity, but it is simply unable to be more than that.

There could be an integrated theory on the Right, where rural and semi-rural places are developed in a traditional style and cities are turned into experimental grounds where the traditional mixes with the new to form a sublime synthesis, ready for the world of the future, but that is sadly not the case yet. Instead, what can be seen to happen is that the Right, enamored (for good reason, might I add) with the splendor of the past, is more concerned with observing and preserving the halls of old palaces and of ancient ruins, like our very own Parthenon, exactly in the state that we find them today, rather than developing any of them. Keep the Parthenon in mind, since it serves as a great example.

I do not want to be misunderstood here, so I will have to clear up a few more possible “grounds” for objection. My intent is not to advocate for a futuristic “refitting” of existing ruins and antiquated landmarks into some modern abomination, nor is it to advocate their destruction or lack of preservation, but I seek to ask the simple question: when we have a building like the aforementioned Parthenon, which has been a ruin for more than 400 years now, why are we only barely making the repairs necessary to keep it as it is?

We are in the era where it is easier than ever to use construction materials that can be added and taken away from a building, without damaging it, and yet we are still letting such a great monument of Classical Greece without a roof? Our arch-screw-up of a prime minister had the opportunity to make such a change early in his tenure, and what did he do? he chose to add “easily removable” cement to the area around the Parthenon, allegedly so people with disabilities could access it more easily. Instead of serving to represent the beauty of this monument as it historically existed, we would much rather make the area around it uglier for tourist ease. This example perfectly represents the problem with modern architectural priorities.

So what do I think should be done with such monuments? For this, we will have to take a detour to the Greek islands of Crete and Rhodes. In Crete, the British archeologist Arthur Evans, alongside his team, discovered the ruins of the Minoan palace of Knossos and restored it splendidly, based on their archeological understanding of how it looked before. It is now one of the most recognizable sites in the country and very popular with tourists. That palace was not the only one though, French and Italian teams excavated another half-dozen palaces of the same civilization dotted around the island and they left them as they found them. If one visits the beautiful palace of Knossos and then goes to the rest of them, they will be left scratching their heads as to why the former is a beautiful and recognizable set of buildings whereas the latter are just a bunch of rocks on the ground.

Similarly, in Rhodes, the old castle and palace of the Knights Hospitaller, a Christian military order who had their base there for a few centuries, was renovated under the direction of the Fascist regime of Italy, during the 1920s and 30s, when the Dodecanese islands were Italian territory for around 30 years.1 Certain professional historians, being nitpickers (as they often are, unfortunately), love to point to the inaccuracies of these renovations, using them as arguments against such attempts at restoration of the past, but the simple truth is that we will never have the foresight necessary to recreate these buildings exactly “as they were”. If anything, we must ask ourselves whether there even is such as thing as “as they were”. Do we know if one ruler or grandmaster moved a vase in the 2nd floor from one side to the other? if we do, which one was the “correct position”? One can clearly see that these are absurd questions. The answer to not knowing fully how a building looked like at a given stage of its history is not to keep it as rubble, but to use our best historical knowledge to give it a “new life” as a living, breathing, embodiment of its era.

Many on the Right continue to suffer under the distortion that if we dare to even touch the “ancient piles of stones” we will somehow ruin the traditional thread that ties our country together, but the reality is that this very “worship of ruins”, long since past their expiration date, is a direct result of our decline, our holding on to a glorious past, in the form of older buildings and objects, is a symptom of our inability to explore, invent and create new forms of greatness, fit for our time.

If the Right wishes to be a force of the future, it will have to move past this urge to mere preservation of the broken. This doesn’t mean that we destroy our history or we lose respect for it, but it means that we are eager to make new history. It means the reintegration of man into the historical cycle again as an active participant, instead of passive victim.

For those interested in the Italian treatment of the Dodecanese, read this: McGuire, Valerie. (2020). Italy's Sea Empire and Nation in the Mediterranean 1895-1945. Liverpool University Press.